Microdon fulgens Added to Vineyard Syrphid Checklist

On the humid afternoon of July 8, 2024, I was photographing pollinators on wild indigo flowers in the West Tisbury section of Manuel F. Correllus State Forest. A flying insect caught my eye as it flew in and landed on a leaf about ten feet from where I was standing. A glance through my binoculars showed an intriguing fly – iridescent green with long, blade-like antennae – so I stalked it and managed three decent photographs before it flew off again.

The distinctive antennae told me that I had found a member of the genus Microdon, in the hoverfly family (Syrphidae) and sometimes known as “ant flies.” Members of a relatively small, poorly known, and infrequently observed genus, Microdon adults, in my limited experience, usually behave like this: unlike most other Syrphids, they rarely visit flowers, and all the ones I’ve observed have flitted restlessly among low vegetation, perching momentarily before moving on. They are not easy to photograph.

The name “ant fly” comes from the larval habits of the genus, which live as predators and kleptoparasites in ant nests. Microdon larvae mimic ant pheromones, fooling their host ants into accepting them in the nest. The genus information page in Bugguide provides a fascinating overview of the biology of this unusual genus.

Later, after reviewing my photographs, I created an iNaturalist observation for my fly, hoping to get some ID assistance. My initial ID was M. craigheadii, the only iridescent green Microdon I could find that appeared likely in southern New England. But subsequent examination of the photos showed details of structure and wing veination that suggested M. fulgens, a species that appeared to be essentially restricted to the deep Southeast. For help, I tagged several of the Syrphid fly experts who have helped me over the years.

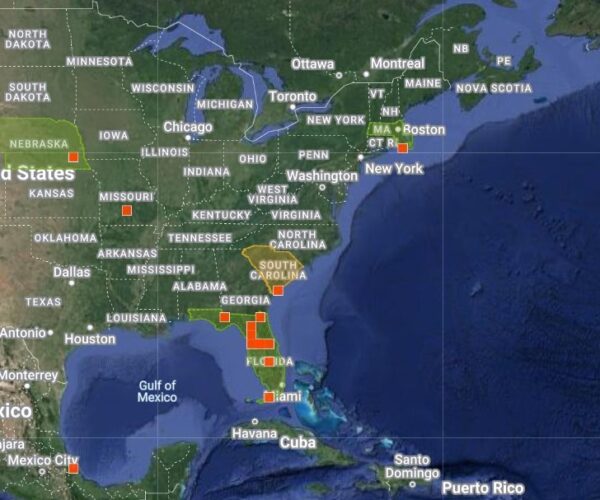

The information I could find on M. fulgens showed no occurrences closer to Martha’s Vineyard than South Carolina. Trina Roberts helpfully linked a range map on a page on the Canadian Journal of Arthropod Identification that showed records from Pennsylvania and New Jersey – still distant, but close enough to make a record of this species on the Vineyard seem plausible. There are also records from Missouri, Texas, and Mexico, and one from Nebraska that may reflect an accidentally transported individual. Two experts, agreeing with my interpretation of my photos, confirmed my fly as M. fulgens, a first Vineyard record and a significant northeastward expansion of the known distribution of this species.

What is Microdon fulgens doing here? It’s a difficult question. Microdon species are strong fliers, and it’s probably impossible to rule out the arrival on Martha’s Vineyard of a vagrant individual from somewhere to the south. But the habitat the fly occurred in seems typical for the species. One of the ant species that is known to host M. fulgens, Polyergus lucidus, occurs on Martha’s Vineyard. And, signficantly, I’ve encountered more than a half-dozen other individuals in the state forest since the initial sighting, including one I was able to photograph during our annual bioblitz of Correllus State Forest on July 20, 2024. So it seems irrefutable that a naturally occurring population exists here, well removed from the nearest extant population (which may be unknown but could certainly be closer than New Jersey). Among insects, this pattern – undetectably scarce for many years, then abruptly quite common for a season – is surprisingly common. It may be years before the species is observed here again.

Microdon fulgens, Correllus State Forest, July 20, 2024

Aboriginally, there may well have been a more or less continuous population of M. fulgens (or, perhaps, of a M. fulgens complex of closely related, essentially inseparable taxa) in suitable habitat up and down the East Coast. (Suitable sites for the fly must also be suitable sites for the host ant, an occupant of dry, open or semi-open habitats.) Habitat loss and interruption of ancient disturbance regimes may have reduced and separated patches of suitable M. fulgens habitat, resulting in a highly fragmented modern distribution.

While that history is speculation on my part, the Vineyard’s distinctive biodiversity lends credence to it. A surprising number of such relict populations, often of species associated with barrens habitats, occur here. These outposts are among the most interesting biological features of the Vineyard and rank high among the most important biodiversity to protect.

Matt Pelikan is the director of the Martha’s Vineyard Atlas of Life program at BiodiversityWorks. A birder since early childhood, he has steadily expanded his natural history interests. Syrphid flies are one of his favorite groups of insects.