MVAL in iNaturalist: 2022 Year in Review

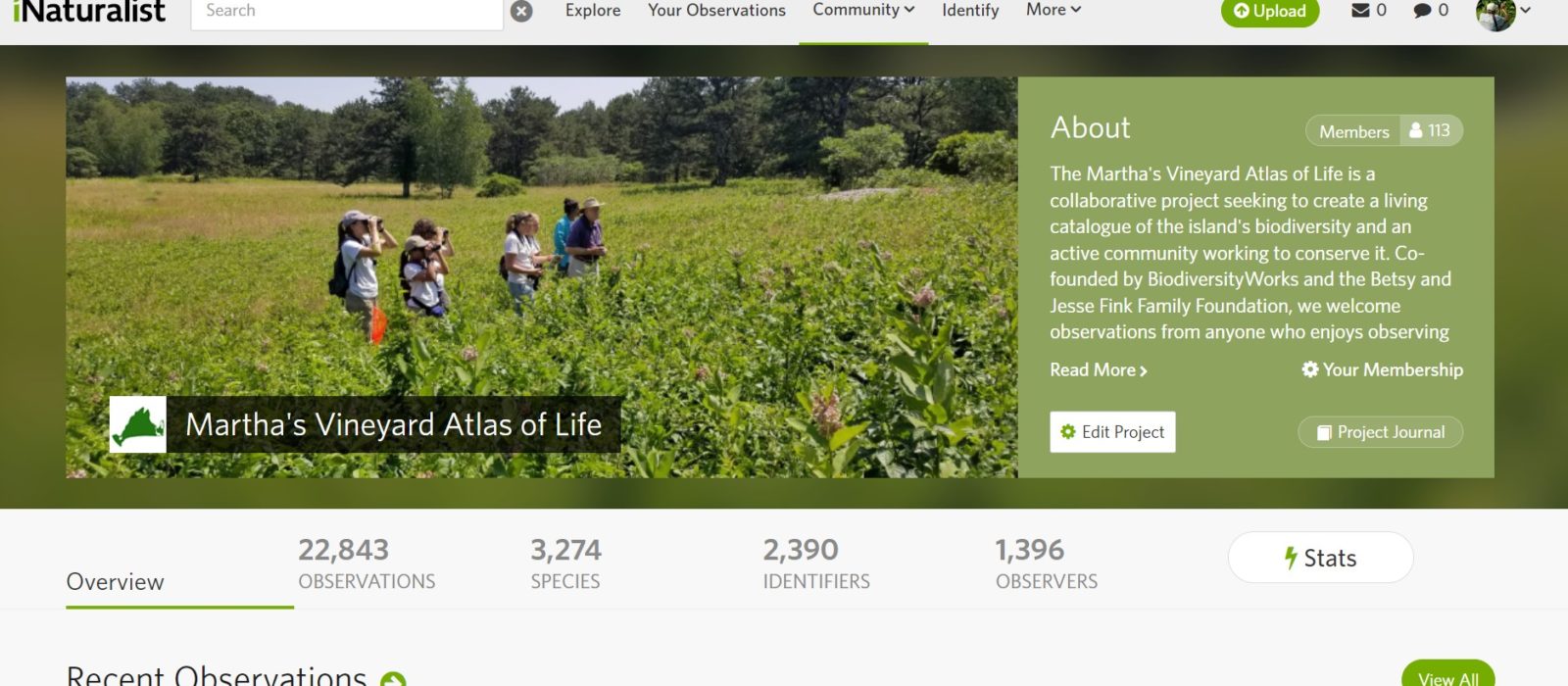

Since its inception in February 2021, the Martha’s Vineyard Atlas of Life (MVAL) at BiodiversityWorks has relied extensively on the community science platform iNaturalist to gather data on Vineyard flora and fauna, and as a means to support and encourage increased interest in the island’s unique biodiversity. With its ease of use, ability to connect naturalists with experts around the world, and sophisticated built-in tools including analytical capabilities and artificial intelligence to assist with identification, iNat has worked very well for the MVAL. At present, almost 23,000 Vineyard observations reside in the MVAL project, and the density of data now makes it possible to assemble checklists for island wildlife based on iNat data and to observe patterns of abundance and distribution with enough resolution to draw meaningful conclusions.

Our iNaturalist project is set up to collect all verifiable observations from a polygon we’ve defined as Martha’s Vineyard. (In iNaturalist-speak, verifiable observations reflect wild individuals and are supported by a date, a location, and either a photograph or a sound recording.) We don’t know how much effect the MVAL’s efforts to encourage iNaturalist use have had, but in 2022, the amount of Vineyard data collected by our iNat project showed impressive growth.

In 2022, the MVAL iNaturalist project collected 9,968 observations – just short of 10,000! – representing 2,261 species. A total of 540 observers contributed data, and 1,062 identifiers helped identify those observations. (If limited to “research grade” observations, these numbers drop to 6,851 observations, 1,652 species, 435 observers, and 952 identifiers. While research-grade observations have been confirmed by at least one person who is not the original observer, there are likely some mistaken identifications among any significant set of research-grade records. And there are undoubtedly many perfectly correct IDs among non-research grade observations that just haven’t yet been confirmed. Since there is no way to accurately quantify how many IDs in either class are actually correct, we’re simply going to use the broader set of all verifiable observations in this analysis.) In 2021, the corresponding numbers were 6,272 observations, 1,923 species, 512 observers, and 696 identifiers. So although the number of observers didn’t increase much from 2021 to 2022, the level of activity of those observers increased by about 59%, and that increased volume of observations meant that we also received substantially more support from identifiers.

For comparison, worldwide, iNat accumulated 30,248,456 observations from 932,503 observers in 2021. In 2022, those figures increased to 34,132,009 observations (an increase of 12.8%) and 931,742 observers. The MVAL project, then, reflected the same modest growth in the number of participants that iNat is exhibiting worldwide. But our level of activity increased more than four times as fast.

The sharp increase in Vineyard observations in 2022 was driven at least partly by the use of iNaturalist for specific research purposes. For example, a project carried out by the MVAL, The Betsy and Jesse Fink Family Foundation, and eight island farms collected 525 observations of animals visiting flowers on farms, representing 139 species. The MVAL also coordinated two “bioblitzes” – intensive, one-day surveys of specific properties – each of which produced a huge pulse of data. An event at The Trustees of Reservations’ Long Point Wildlife Refuge on June 17-18 produced 477 observations representing 289 species. A bioblitz at The Nature Conservancy’s Hoft Farm Preserve July 15-16 produced 574 observations and 279 species. Because observations can be listed in multiple projects in iNaturalist, all of these observations also feed into the MVAL project. Taken together, the three projects garnered 1,576 observations.

Bioblitzers at Long Point

Many 2022 observations were of conservation significance, adding to our collective knowledge of the status and distribution of species of conservation concern. In 2022, 30 species in the MVAL project were tagged by iNat as “Threatened,” a designation that can reflect listing under a state or federal endangered species act but which often reflects an assessment by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Many species deemed at risk by the IUCN are listed as such because of declining numbers across their range; some of these, though, remain locally common (Common Grackle, Quiscalus quiscula, is one surprising example of an IUCN “Threatened” species). Still, collecting data on these species is important because it contributes to a deeper knowledge of their status.

Our iNat project also collected 2022 observations of at least five species listed specifically under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act (MESA). We may have missed some species, because iNat’s method for assigning “Threatened” status is quirky and there is no efficient way to search for species that are listed by some entities but not by others. But we did find 2022 observations for Eacles imperialis (Imperial Moth), Threatened; Cicindela purpurea (Purple Tiger Beetle), Special Concern; Barn Owl (Tyto alba), Special Concern; Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus), Special Concern; and Least Tern (Sterna antillarum), Special Concern. Aside from the Peregrine Falcon, all of these observations reflect breeding populations on Martha’s Vineyard, highlighting the island’s role in supporting species that are rare in Massachusetts.

Nearly all of the verifiable observations in 2022 were supported by photographs. A total of 29 observations, however, were supported at least in part by sound recording. These are of birds, tree frogs, Orthoptera, and cicadas (here’s an example). Many iNat users don’t know that sound recordings can be used to support observations (video, unfortunately, cannot at present). But with effective microphones in most types of smartphones and the ready availability of “voice recorder” apps that allow for easy basic editing of sound recordings, getting sounds into iNaturalist is easy. We encourage all iNat users to keep this tool in mind since it makes it easy to document types of wildlife that are easier to hear than to see.

Insects accounted for almost half the observations in 2022, 4,563 representing 949 species. Plants were also well represented, with 3,277 observations of 780 species. We collected 769 bird observations of 145 species in 2022 (Herring Gull was the most frequently reported species). Reflecting the difficulty of observing them, ray-finned fishes only accounted for 63 observations, of 24 species. Some of these were pretty bizarre: a Planehead Filefish (Stephanolepis hispida) found in Chilmark was near the absolute northern limit of its range and is a species more associated with coastal waters from North Carolina southward and in offshore waters near the Continental Shelf edge. This individual was likely carried here by the Gulf Stream. We had only 73 observations of reptiles, reflecting nine species, showing a pressing need for more information about these species, many of which are believed to be declining on the Vineyard.

Common Snapping Turtle (photo by Lucy Keith-Diagne)

The most frequently reported species overall in 2022 was the Common Eastern Bumble Bee, Bombus impatiens, represented by 126 observations. Twenty-three observers contributed sightings of this bee, though 91 observations came from a single observer and 48 came from the above-mentioned farm project.

Common Eastern Bumble Bee, Bombus impatiens, on goldenrod

Rounding out the top five most reported species were Western Honey Bee (Apis mellifera), Monarch (Danaus plexippus), Ligated Furrow Bee (Halictus ligatus), and American Copper (Lycaena phlaeas).

The level of activity of individual observers varied widely. I’m somewhat embarrassed to mention that I contributed 2,582 MVAL observations in 2022, more than a quarter of the year’s total; I guess you now know what I do in my spare time! Botanist and Polly Hill Arboretum Research Fellow Margaret Curtin was also highly prolific, contributing 858 observations. Two badly under-studied groups, mosses and lichens, figured prominently among Margaret’s observations, and she also contributed many observations of rare or poorly-documented plants. Seventeen observers contributed 100 or more records. At the other extreme, 212 observers contributed only a single observation. Even the least active observers, though, have contributed to our understanding of Vineyard wildlife. And we expect that many observers at all levels of activity will increase their participation over time.

Finally, it’s important to consider the roles that identifiers play in iNaturalist, providing identifications when observers are unable to and correcting or confirming observations that observers or others have provided. It’s an important way of ensuring the quality of data in iNaturalist, and the many experts who contribute their knowledge to iNat are providing a vital service. While our most active observers, unsurprisingly, also provided the most identifications (1,774 by me, 1,662 by Margaret), a total of 2,839 people around the world, many of them world-class experts, contributed at least one observation to the MVAL project in 2022. For example, bee expert John Ascher, based in Singapore, provided 474 bee identifications for the MVAL project in 2022. Dr. Ascher’s iNat profile shows he’s made only nine observations – but he has provided more than one million identifications for bees around the world! You couldn’t ask for a better example of the generosity and collaborative spirit that makes iNaturalist so successful.

All in all, 2022 was a great year for the MVAL and for our iNaturalist project. We’re grateful to everyone who has helped us out, including iNat observers, identifiers, and bioblitz participants. And we look forward to another year of growth and interesting sightings in 2023.

Matt Pelikan is the director of the Martha’s Vineyard Atlas of Life at BiodiversityWorks.